The Glenbawn Dam rumour and the 1955 flood

Big floods often spark wild speculation about their causes, and the great Hunter River flood of 1955 was no exception. A rumour that developed during the flood and has survived to this day is that the severity of the event, or perhaps even the event itself, resulted from the blowing up of Glenbawn Dam above Aberdeen.

Andrew Burg’s article about Glenbawn Dam

One of Maitland’s local historians, the late Andrew Burg, was a resident of Maitland in 1955. No doubt he heard the rumour, the source of which is not known; moreover he appears to have believed it. Many years later, in 1990, he wrote a short article which sought to explain why the dam had been detonated. His piece listed the circumstances in which the explosion supposedly occurred, the people he thought were responsible and the organisations to which they belonged.

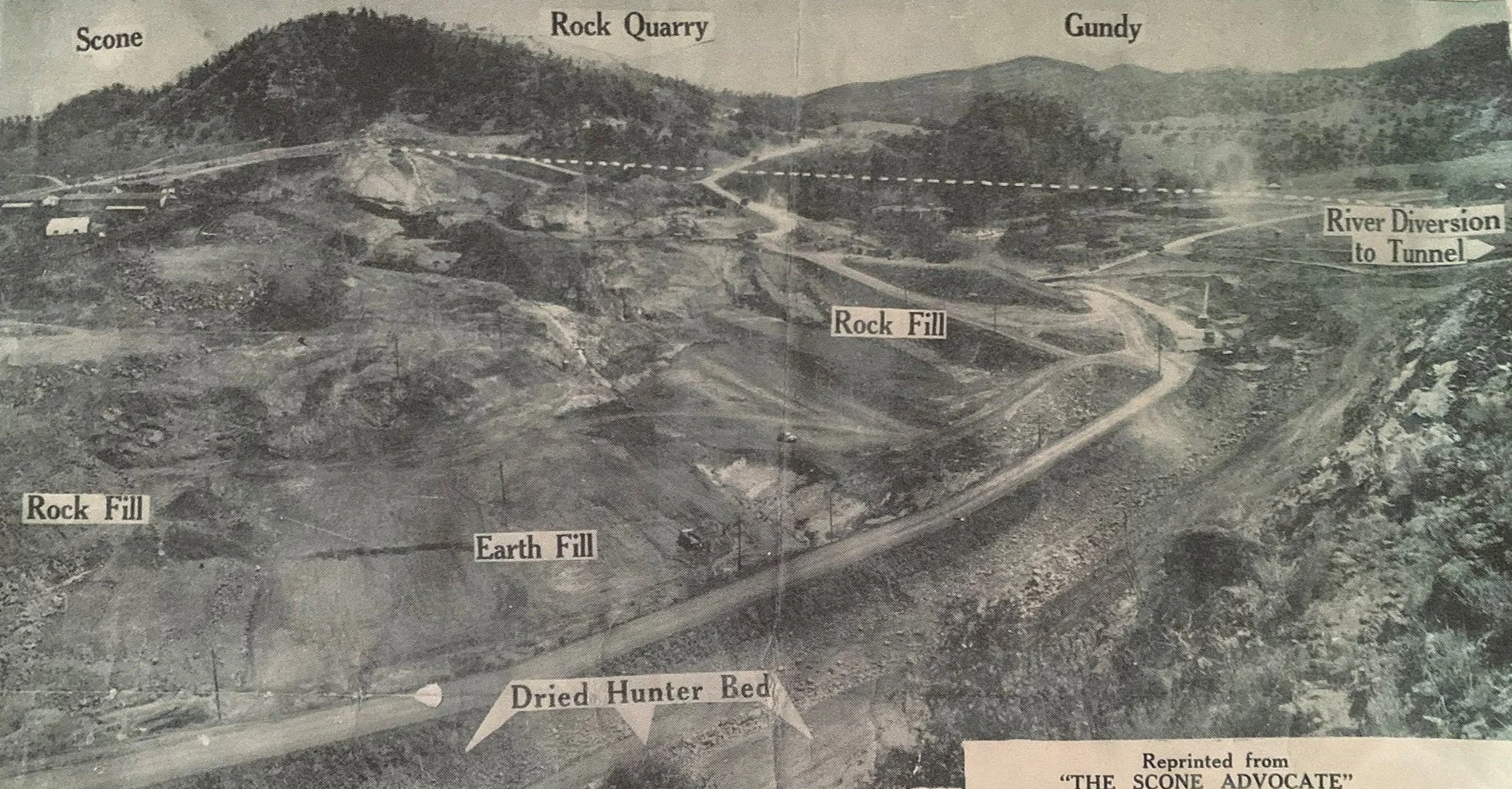

The piece contains several errors, and the evidence that his account is not factually accurate is compelling. First, Burg claims that the dam was completed in 1952, but in fact its construction was completed only six years later and it stored no water until 1958. The accompanying panorama shows this. The photos that made it up were taken for the Scone Advocate only a couple of weeks before the flood and the panorama was published the following year.

Panorama of the Glenbawn Dam site, February 1955

(Scone Advocate, 1 June 1956, courtesy Muswellbrook Chronicle/Hunter Valley News)

In February 1955 work on the dam was not far advanced. The panorama incorporates a dotted line where the dam’s crest would eventually be: that line was far above the work that had been completed at the time the photos were taken. The dam’s foundations had been built and a diversion tunnel created, but little more. So the volume of retained water could only have been minimal and would have contributed almost nothing to the flood.

In any case it is not clear how blowing up the dam, had it existed, would have reduced the downstream impacts - unless the detonation was carried out very early in the flood when the amount of retained water was small. Logic suggests that any sudden release of a large volume of water would have exacerbated those impacts, especially a short distance downstream before the released ‘wave’ had attenuated. The impacts on Aberdeen and Muswellbrook would have been disastrous.

Moreover some of the officials who, according to Burg’s account, met and made the decision to blow up the dam did not exist in 1955. He refers to a senior officer from the ‘Flood Mitigation Authority’, but there was no such organisation in New South Wales at the time of the flood. Only afterwards were the Water Conservation and Irrigation Commission (WC&IC) and the Department of Public Works made responsible for flood mitigation activity in the state. Public Works was given carriage of the task in areas below the tidal limits on the rivers that flowed to the Tasman Sea, including the Hunter, and the WC&IC was made responsible above those limits.

Over the following years those two organisations built many kilometres of levees in the Hunter Valley: Public Works from Oakhampton downstream to below Raymond Terrace and the WC&IC at towns further up the valley including Singleton, Muswellbrook and Aberdeen.

Next, Burg cites the leader of the ‘Civil Defence Authority’ as one of the men who attended the meeting at which the decision was made. That organisation too did not exist in February 1955. It was established three months later, to promote civil defence in the event of Australia being hit (perhaps with nuclear weapons) in a potential and at the time feared war between the USA and the USSR. The New South Wales State Emergency Services organisation was formed at almost the same time for the purpose of managing the effects of floods.

These two organisations were merged early in 1956 to become the Civil Defence Organization and State Emergency Services. This agency is now known as the State Emergency Service but it is usually referred to as the SES. The SES has legislated responsibility for co-ordinating real-time community responses to floods.

It can, on the evidence, be asserted that the blowing up of Glenbawn Dam did not occur. The rumour gave birth to a myth which is still believed by some people.

For years, Burg’s well-meant and honest attempt to explain the greatest flood in Maitland’s history (or at least its severity) has been cited as proof that the rumour had substance. His article appeared on the wall of a doctor’s surgery near the Maitland Courthouse where it has probably been read by hundreds of people. No doubt this helped to perpetuate the rumour and solidify its provenance.

Andrew Burg

(Peter Bogan Collection)

The lessons of Glenbawn Dam

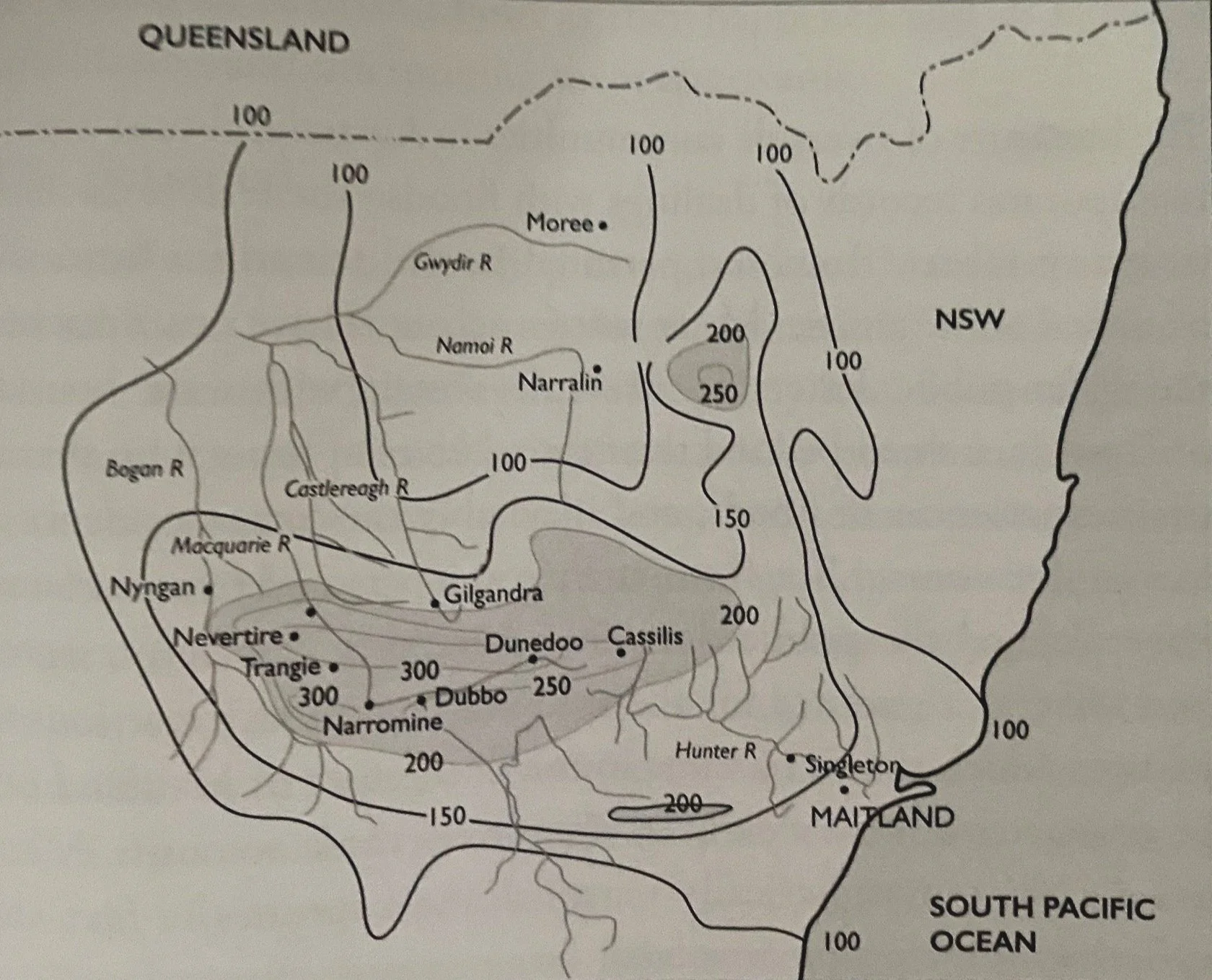

That the blowing up of Glenbawn Dam in 1955 is still taken by some to have occurred in actuality demonstrates how misinformation about the causes of natural disasters can persist thanks to well-intentioned but misguided attempts to explain events. The great flood was brought about by very heavy rain, especially over the Goulburn and upper Hunter rivers. Gelignite was not used to blow up a structure that barely existed beyond its foundations.

Rainfall isohyets, 1955 flood, showing the amount of rain over the catchments of the Hunter River and the NSW tributaries of the Darling River

(Bureau of Meteorology)

Some works at and near the site of the dam (including an earth bank built to divert the river, a means of de-watering the site) were damaged by the great volume of floodwater from upstream, but those elements of the dam itself that had been constructed were little affected according to an account of the dam’s construction by CT Stafford and DC Weatherburn, two engineers who were involved in the project. Indeed no mention of any detonation of the dam appears in their report. Conspiracy theorists might suspect a cover-up here, but the photograph taken for the Scone Advocate (above) just prior to the flood is compelling evidence that at the time there was no dam in existence to blow up.

Andrew Burg died in 2000. During his life he made a substantial and worthy contribution to the recording of Maitland’s history, and the Andrew Burg Collection of documents and essays held in the Maitland City Library is a valuable resource for students of that history. He holds an honoured place among Maitland’s many talented and industrious local historians and his compilation has been utilised by many. But his account of the decision to blow up Glenbawn Dam and thus cause or exacerbate the flood of 1955 is clearly in error.

The persistence of the rumour and its place in local folklore probably prompted Burg to examine its authenticity years after the flood. In trying to work out what had happened he must have become one of the many who came to believe the rumour. Then, in writing up what he had concluded, he unwittingly contributed to the perpetuation of an erroneous explanation of the flood or of its severity. This was unfortunate: it is important that people understand events in history and not be misled by misinformation.

Jokes, presumably, are created and transmitted much as rumours are. The details of their origins are usually unknown but the transmission from person to person is easily understood.

Other flood myths

It is very likely that the rumour was and is believed by some because they find it hard to come to grips with the sheer scale of the 1955 flood on the Hunter River. Nature, they might think, could not produce a flood of the size of that one, well beyond anything that they had ever seen there (or indeed has been seen there since). A human hand - in this case causing the supposed destruction of a dam - might have helped give credibility to the explanation of what people experienced. There is a lesson here on the power of nature: it does not necessarily need human involvement (or for that matter divine intervention) to bring about disaster. Extreme events are part of nature itself.

The Glenbawn dam myth is a recurrent theme in Maitland’s flood history. Other myths sometimes mentioned are the alleged dynamiting of the Oakhampton embankment in 1955, leading to the destruction of twenty-one Mount Pleasant St houses and a tit-for-tat dynamiting of the levee protecting Lorn. No clear evidence has ever been produced that the breaches of these levees were caused by human actions, and there were no prosecutions.

Then there was the rumour of the blowing up of the road on the Oakhampton embankment in 1971, and a similar rumour developed in 2007 when people downstream heard a loud noise at the moment Oakhampton Rd gave way at the same place. They thought the noise was the result of an explosion. In both cases Oakhampton Rd was washed away with a loud ‘whoosh’ as the floodwaters broke through.

All these cases had ‘natural’ causes. There was no need to call upon the extraordinary, or indeed human action, to explain them.

A forensics expert, Neil Raymond, examines the breach in the Oakhampton Road in 2007

(Maitland Mercury)

There was a supplementary myth relating to Glenbawn Dam in 1955, probably developing decades afterwards, when it was suggested that the flood had been exacerbated by the opening of the dam’s gates ‘at the wrong time’. But Glenbawn, like most dams in New South Wales, does not have gates: it has a spillway over which water is designed to flow when it reaches the spillway’s level which is well below that of the crest of the dam.

Many people came to believe that Glenbawn Dam was blown up to ‘save’ downstream communities including Maitland. To this day some cite individuals, including relatives, who they ‘know’ caused the event or witnessed it. This is a not-uncommon feature of community memories about disasters: people apparently want to associate their relatives or other people they know or knew with significant events that occurred. Some people even imply that they themselves were involved in events, despite their not possibly having been there. In some cases they are seeking to claim some sort of ‘credit’! This is an intriguing element of the psychology of disasters.

Errors such as the ones made by Andrew Burg in his 1990 article are not uncommon in the writing of history. Historians rarely have all the relevant facts available to them, and rumours, never thoroughly addressed in their early days, can be taken as fact to fill in the gaps. They can help historians to develop their narratives and make them comprehensible, but mistakes sometimes creep in as the accounts are developed.

References

Burg, Andrew ‘The Glenbawn Dam explosion’, unpublished manuscript, 1990 (held in the Andrew Burg Collection, Maitland City Library).

Keys, Chas, In Times of Crisis: the story of the New South Wales State Emergency Service, Focus Publishing, Bondi Junction, 2005.

Keys, Chas ‘Our past: the Glenbawn Dam myth’, Maitland Mercury, 10 March 2023.

Maitland Mercury

Scone Advocate, 1 June 1956.

Stafford, CT and Weatherburn, DC, ‘Glenbawn Dam Construction, The Journal of the Institution of Engineers Australia, 30/12, 1958, pp333-51.