A village on the river: Horseshoe Bend

One of the striking characteristics of old Horseshoe Bend was its self-contained village nature. The population of the Bend was never large, peaking at about 1500, so it was easy to know everyone and everything about everyone. Its geographical containment within a larger urban area, however, and its lack of access (until 1920 only through Hunter St and then through Hunter and James streets) set it apart.

The nineteenth century

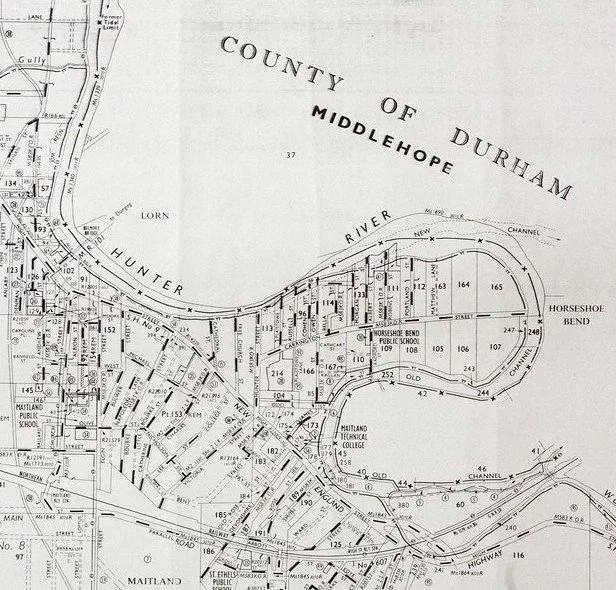

Map, Parish of Maitland, March 1885 - detail showing Horseshoe Bend contained by the Hunter River.

Horseshoe Bend’s contained nature led to a strong ‘us vs them’ attitude which took precedence over differences one would expect from the social, economic or religious diversity of its inhabitants. It was a very polyglot community. Irish Catholics, somewhat over-represented, mixed amicably with English Anglicans and Scottish Presbyterians and a smattering of other nationalities and denominations. There was a lot of structural bigotry but at the personal and community levels things were usually harmonious. One notable exception was the McIntyre Riot of 1860 which saw the Catholics of the Bend play a starring role.

As well, the highest-ranking people mixed with their employees. In the 1870s there were five professionals living in the Bend along with many small shop owners in the commercial category but bigger merchants as well. There were many skilled tradesmen and only 20% of the working people were low-skilled or labourers. This mixture can be seen in the extant housing especially, for example, in Robins St.

Within the community one could hate the bloke up the road, or think him a toffy-nosed git, or call him a Proto Mason. But if an outsider belittled him, then all in Horseshoe Bend sprang to his defence. Equally, if danger threatened (like a fire or a flood), neighbours sprang into action regardless of their friendship or animosity.

The Bend rapidly morphed into an almost exclusively native-born community, the result of remaining a very closed and intergenerational village. Many of the houses, often small, accommodated three generations of the same family. Those forced out of home by sheer weight of numbers did not move far. Multiple family members lived in close proximity to each other and their parents. Often neighbours married and moved into homes close to both parents.

All the land was privately owned so it was easy to purchase (rather than being subjected to the convoluted Government tender process) and could be easily subdivided to accommodate children leaving the nest. Families were often large, regardless of religious affiliation. The Anglican Charles Robins (of Robins St) had seven children while the Catholic John Bogan, the antecedent of the late Peter Bogan (a local flood expert), had eight. These were modest-sized families for the times.

For many the Bend came first and Maitland second. Facilities in the Bend were built and supported because ‘others’ controlled the Maitland equivalents (schools, churches and sports clubs, for example). They were quick to claim any person who rose to fame (or notoriety) as theirs. George Moore, the famous cricketer, for example, lived in Robins St, and he was rowed through floodwaters by a Bend crew to ensure he made it to an important inter-colonial game. In 1862 Moore almost single-handedly in a team of New South Wales and Victorian cricketers defeated a touring English side through his batting and baffling spin bowling.

George Moore, 1876 (Cricket Country, 9 Nov 2015) and two of his houses in Robins St (reproduced in Hunter, 2000, p103).

The house in the middle, ‘Outward Cottage’ possibly dates from the 1870s and the one on the right, ‘Amphill Villa’, was designed by JW Pender in 1884. (Hunter, 2000, p103)

(click on above images for larger views)

Horseshoe Bend residents developed skills suited to their needs. Its floodboat teams were renowned for their skill and bravery, saving multiple lives and people’s belongings from impending doom in flood time. Flood relief was a total community effort. People gathered at the old Port Maitland Inn to provide and receive food, clothing, furnishings and money, and to assist in the rebuilding of homes. In 1862 a baby was burnt to death in Victoria (now Morgan) St and the house destroyed. The father was the sexton at the Wesleyan Chapel but nearly everyone in the Bend (Anglicans, Catholics, Presbyterians and others) contributed to his rebuilding subscription.

As well as its large core population, Horseshoe Bend was home to many hundreds on a short-term basis. Despite the crowded houses there was always room for a paying boarder. This was usually a single man or woman (often very young) working locally or a recently married couple. This characteristic continued into the early twentieth century. In 1930 at least 10 of the 19 houses in James St had a boarder with another five having two couples living in the same house.

Many people found little incentive to move outside the Bend. It had everything they needed for basic life. Most importantly it had plenty of water (too much on some occasions!) and tanks and latrines were easy to build and worked efficiently. Building blocks were readily available and the area was well serviced. By the 1870s it had its own small shops (and close access to many others) and two pubs. Three other pubs in High Street were strongholds for Horseshoe Bend men.

Port Maitland Inn, Plaistowe St, Horseshoe Bend, 1894 - one of the two pubs in Horseshoe Bend

(HF Boyle collection, reproduced in Hunter, 2001, p 14)

Small farms (of less than two acres mostly growing fruit, vegetables and supplying milk and eggs) and butcheries could supply most people’s food requirements on a daily basis, necessary in pre-refrigerated times. Almost all employment was local and often within Horseshoe Bend itself. The place had two churches, an infants’ school which acted as a community centre and meeting place, and multiple sporting facilities including a cricket oval, a rowing club and swimming pool (the floating baths in the river).

Horseshoe Bend Infants School, 1914

(source unknown)

All the cultural and social facilities you could ask for existed within easy walking distance, including theatres, libraries, lodges, the showground, the racecourse, municipal buildings and colonial agencies.

In the nineteenth century, Horseshoe Bend’s residents were a multi-generational mix of different religions, races and socio-economic levels. The area was residential, but with commercial and manufacturing activity as well. Floods after the 1893 flood almost destroyed the village structure as the better off people moved to higher areas, taking their factories and businesses with them. The river’s course changed and left businesses, like Cohen’s, isolated. The CBD moved west along High St away from the Bend. Multiple floods, especially those of 1893, 1949 and 1955, afflicted the community and caused change.

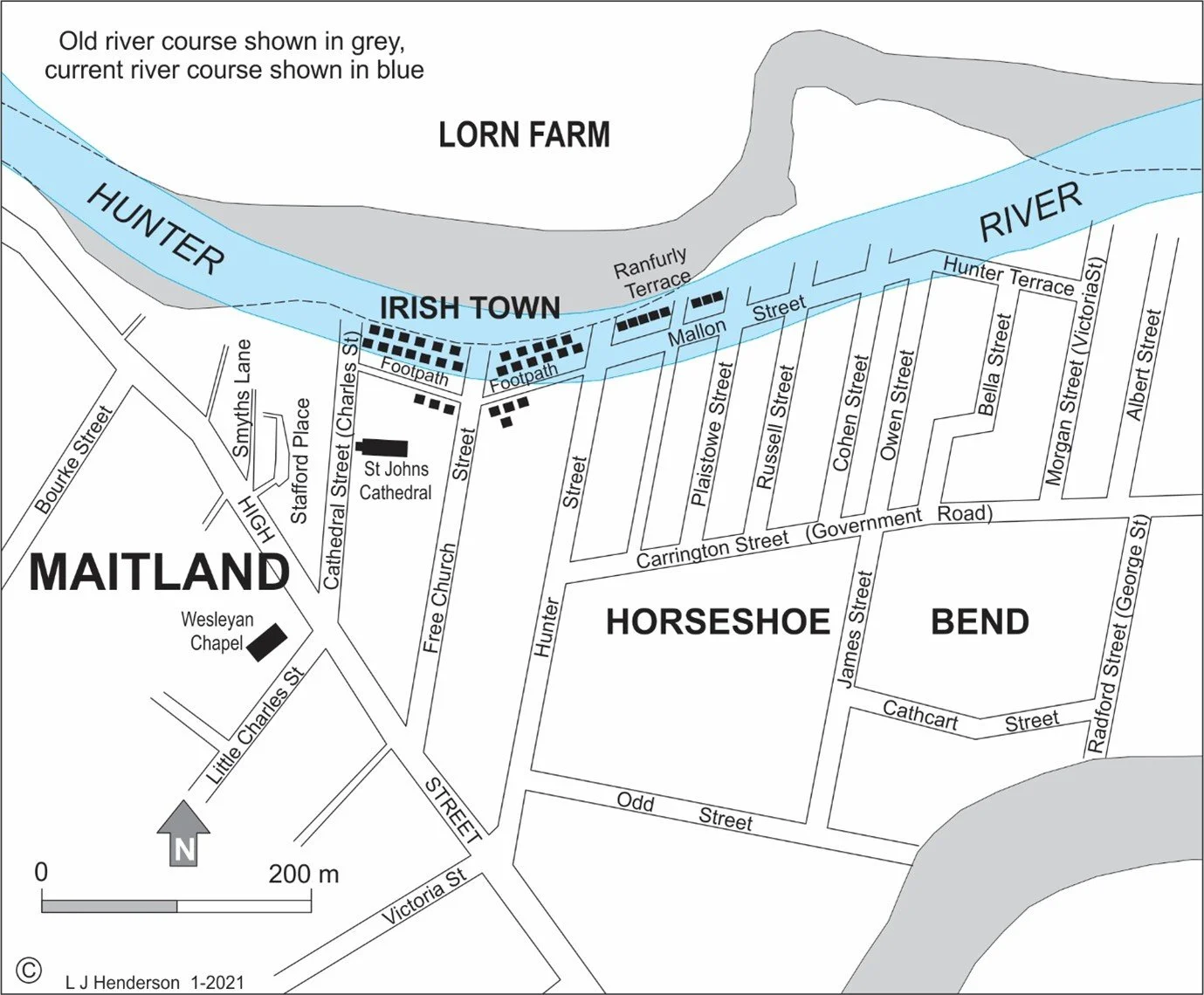

Map of part of Horseshoe Bend and Irish Town

(Lawrence Henderson, 2021)

The twentieth century

The Bend rapidly became a dormitory suburb, losing local workplaces. By 1909 no professionals (other than a few teachers) lived in the area, the proportion of employees (largely shop assistants) had risen dramatically and the proportion of skilled tradesmen had declined. Miners first appeared around the beginning of the twentieth century.

The world was changing. Goods that were previously produced locally were now manufactured further afield (for example in Sydney) and imported by railway or by road. These trends continued right through the first half of the twentieth century.

The Bend still maintained many nineteenth century characteristics, in particular the multi-generational proximity of family. Everybody still knew everyone. Children of the 1960s and 1970s often spoke of taking refuge with an uncle, aunt or grandparent when in strife at home. Extended families often sorted out squabbles between neighbours’ children.

And the area still gathered its people into a Bend mentality. The First World War was a classic example. The Bend people lauded their very local heroes and even struck their own commemorative medal given to all returned Bendites and to the families of those who had been killed in battle. Some honorary Bendites were also bemedaled.

Left: Horseshoe Bend Medal (Harrower Collection)

Right: Horseshoe Bend Infants’ School Honour Roll (Monument Australia) - 31 names are listed, of these 13 were killed in action.

Portland St illustrates some of the character of the Bend and the change that occurred in the twentieth century. Just before the 1955 flood it contained housing, fuel and carriers’ depots, horse paddocks, trotter and dog-breeding establishments, and flower farms. The street had twenty houses with 22 children within a five-year age range forming a close-knit street ‘gang’. One house had three generations living together (parents, a married daughter, her siblings, her spouse and their children). Sixteen of the houses had other close relatives living in the Bend and only three households had no relatives living in the Bend. Three extended families occupied nine houses in the street.

By 1955, however, few Portland St people worked in the Bend. Most men worked in mines, the Burlington Mills (Rutherford) or the BHP (Newcastle) and commuted, often by bicycle. Women worked in the house.

Benders were still strongly defensive and protective of their members. Newcomers who upset locals could expect retaliation. In the 1920s a minor riot, led by third- and fourth-generation boys of the Sellars, Duggan, Varley and Greedy families, threw fence pickets onto the roof of a Carrington St newcomer over some triviality. All were prosecuted - but the newcomers left the area.

One ex-Bendite woman tells of being courted by an East Maitland man in the early 1940s. She had to go to the Volunteer Hotel (on the corner of Hunter St and High St) to escort him to her home in Cohen St so as to ensure he was not expelled. Many girls and young women returning home were met at the Volunteer, bade farewell to their escorts and were guided home to ensure ‘strangers’ (especially South Maitlanders) did not ‘accost’ them.

Volunteer Hotel, corner High and Hunter Streets, c1909 and 1940s

The building on the right dates from 1940. It was burnt down in 1971 along with the neighbouring Capper building.

(click on above images for larger views)

The 1955 flood forced the most radical physical and social restructuring of Horseshoe Bend. Half of the houses and many long-standing families were assisted to move to higher ground: hence the many vacant blocks in the area today which once had houses on them. The earlier tradition of supplying accommodation to short-stay people continued as those that left were replaced by others who stayed long enough to save for a better home. These were often European migrants from the Greta Camp. Housing stock was in poor condition and, until recently, the council refused to allow any work that would prolong the life of a residence. This was a real problem in an area where houses had been and were periodically flooded. Some continued to collapse or were rendered uninhabitable. By 2011 only about 400 people resided in Horseshoe Bend, down from more than three times that number at the area’s peak.

The Bend today has many charms and advantages, but it isn’t the old Bend.

References

Belcher, Michael, ‘Our past: Horseshoe Bend had it all for lucky residents’, Maitland Mercury, 4 February 2022.

Belcher, Michael, ‘Our past: Horseshoe Bend - the twentieth century’, Maitland Mercury, 11 February 2022.

Hunter, Cynthia, Horseshoe Bend, Maitland: Historical Study, Prepared for Maitland City Council, December 2000.

Hunter, Cynthia, Horseshoe Bend Maitland, Maitland City Council, 2001.