The Chinese gardeners of Maitland

On 19 January 1937, six mourners accompanied the body of Ah Tui (or Charlie R Dow, otherwise known as ‘Charlie No Chin’) to his grave in the Church of England Cemetery at Campbells Hill. His death, at 100, removed ‘the last of the Chinese gardeners in the Maitland district’. (Newcastle Morning Herald, 20 January 1937).

The gardeners and their contribution

The Chinese market gardeners contributed mightily to the welfare of Maitland people for over 50 years but they were always, even before the White Australia Policy, considered ‘aliens’ and given none of the support (like the old age pension) available to white Australians after Federation. Ah Tui’s death illustrates this. According to the Maitland Mercury,

Death was due probably to senile decay, prompted by malnutrition and coronary heart failure. (Maitland Mercury, 25 January 1937)

He had lived in a hut at the back of a house in Walker St, South Maitland for some 30 years and the owner of the hut

used to give the deceased a few shillings a week and buy him some meat. Other people used to give him bread and other things. (Maitland Mercury, 25 January 1937)

Somehow Ah Tui must have been trapped in Australia, unable to raise the fare home. One suspects that he was a hired labourer brought to the gardens by a partner in a property. It was such partners who made the money and made frequent trips back to their homes. Yick Lung, for example, a partner in a garden first in Maitland, then at Singleton for 14 years, left for China as late as April 1923. His destination was Canton, where he had a wife and family, and he expected to return to Australia about Christmas. Yick Lung had visited China a few years earlier, staying eleven months (Maitland Mercury, 13 April 1923). By 1923 this was a highly dangerous move as he could have been refused re-entry under the White Australia legislation enacted soon after Federation.

It’s hard today to imagine a diet with no greens and other vegetables but, until the Chinese market gardeners arrived in Maitland in 1868, that was exactly how it was. If you wanted anything other than meat, potatoes, corn, cabbage and some pumpkin, you had to grow it yourself or gather wild vegetables such as Warrigal Greens (a native spinach Tetragonia tetragoniodes). Mr Scobie grew some on his farm at Oakhampton but they played second fiddle to his vines and wines. Diets were light on green vegetable, so the efforts of the local Chinese gardeners contributed to the improvement in the diets and health of the residents of Maitland. Health benefits must have followed.

Chinese vegetable hawker, c1897

The Maitland Mercury of 7 August 1868 waxed lyrical about the wonders of Telarah’s first acre and a half Chinese Garden. The vegetables consisted of cabbages, cucumbers, snake beans, eschalots, onions, turnips, sugar beet and other more common vegetables (presumably potatoes and pumpkins) as well as tomatoes, rock melons and watermelons. The neatness, the total lack of weeds, the raised beds, the use of various ‘fertilisers’ (presumably including nightsoil carried by council-employed pan men from Maitland outhouses to the gardens) (see also Maitland Mercury, 17July 1884) and the continuous watering from hand-held cans all contributed to a revolution in agriculture.

These things showed what industry, energy, skill and perseverance could achieve. The Chinese gardeners had enterprise, and despite periodic racist commentary, this was sometimes recognised. In 1894, for example, the Maitland Mercury referred to the Chinese gardeners near the location of today’s Paterson railway bridge as

industrious and persevering traits of their character . . . are an example . . . to some Europeans. (Maitland Mercury, 9 October 1894)

Methods and locations

While they usually stuck to their tried and true methods, the Chinese gardeners did sometimes respond to needs in original ways. In 1895, for example, during a prolonged drought, the gardeners along Wallis Creek:

. . . set to work and constructed a Californian pump in a rough manner, it is true, but to all intents and purposes as good as one of a more finished variety. Then they made a wooden flume under the road way and dug a series of drains by which the water when it passes out of the flume runs by gravitation to the different parts of the garden. The whole affair is worked by horse power, and the water is lifted out of the creek about 23 feet. (Maitland Mercury, 25 June 1895).

The California Pump

For the 40 or so years after 1868, other Chinese gardens, all on leased land, sprang up at Fishery Creek, Paterson, Greta, Branxton, Victoria Bridge, Tenambit, Morpeth, Narrowneck and Phoenix Park. At the biggest and best, on the corner of Louth Park Rd and Park St, over 20 men tilled ten acres. In most cases they were all partners, sharing the profits and accumulating cash to return to China or to send back to their families. Those who did very well also recruited labourers from within the Chinese community in Australia or back in the homeland such as, one suspects, Ah Tui. They lived in sheds, sometimes three or four in the one room, on a 24-hour roster gardening in the day and delivering produce to the markets through the night.

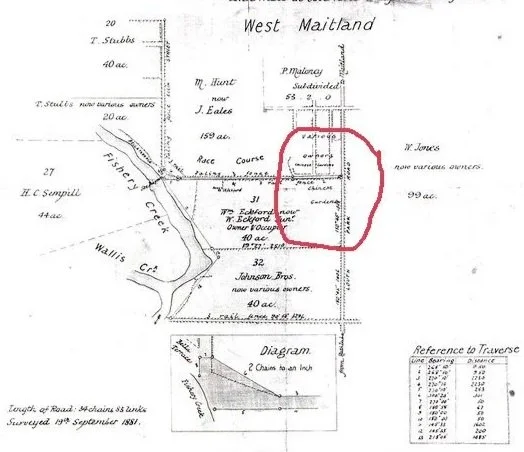

An 1881 map showing a proposed road (Park St) and the location of Chinese gardens, South Maitland.

(Picture Maitland)(image of original at Picture Maitland)

Many had come to Australia to mine for gold but rapidly realised that there was more gold in vegetables than in the ground. As the Mercury early noted:

[One] visits the town every morning, bearing a couple of baskets well laden, slung on bamboo cane across his shoulder, and brings in from 15s. to 30s. per day; and of course sales are made on the premises . . . they are very well satisfied now with the remuneration their toils meet with” (Maitland Mercury, 7 January 1868).

As their market grew and their product increased they turned to human- or horse-drawn carts and toured the suburbs, haggling over prices with housewives and maids. When the Farmers Union Markets were established, in Steam St, Maitland, they sold to the rest of the Hunter Valley and to Sydney.

Problems faced

The Chinese survived a succession of floods and droughts. In May 1870 the Mercury lamented the scarcity of vegetables after the 1870 flood and noted:

The two Chinese gardens are, we believe, abandoned completely. The one on the East Maitland road has lost all pretensions to cultivation of any kind, all the currents from the higher floods having taken a direction over it; and the one on Campbell's Hill has also been destroyed almost entirely by successive submersions by the back water. (Maitland Mercury, 28 May 1870)

Reading the reports today, you wonder how they survived not just the alternating floods and droughts, but also the European Australians. They did not mix well, didn’t drink or carouse (they were allowed their then-legal opium) and did everything they could to keep the peace. They even respected the Sabbath: Ah Tui, for instance, never worked and refused to serve customers on Sundays. Their festivities with crackers, at New Year especially, were a sightseer’s delight (see the Maitland Mercury, 7 March 1893). They were also generous donors to the Maitland Hospital (Maitland Mercury, 30 July 1880).

These were positives, but especially during the White Australia Policy debate they were pelted by youths (Maitland Mercury, 7November 1885), attacked by drunken men (including a vicious rape on one of their women) (Maitland Mercury, 11 March 1890), abused by upset housewives, constantly raided by thieves looking for stashed coin, and had their crops destroyed. They were accused of living in unsanitary conditions (Maitland Mercury, 29 November 1890), befouling their produce with dirty water, polluting the air and water with noxious substances (Newcastle Morning Herald, 16 October 1876), introducing leprosy (Maitland Mercury, 23 February 1872) and a plethora of other sins.

They were also accused of undercutting the local farmers, and in Greta, this was taken up by the resident miners. An anti-Chinese public meeting was held at Greta in 1888 where the gardeners were accused of destroying local farmers. The miners imposed a boycott but this backfired when the gardeners refused to sell to the miners’ wives who told their menfolk to raise the boycott ꟷ or else (Maitland Mercury, 26 June 1888).

The abuse didn’t destroy them, but the White Australia Policy did. It made it nearly impossible to recruit suitable labour and to visit China and return. As well, mechanisation, irrigation and land consolidation ensured that Maitland’s farmers could plant and harvest huge crops of vegetables that had previously been impossible to tend. Labour shortages during the First World War accelerated the mechanisation. Repatriated soldiers, along with the Chinese, found a return to agricultural labour very hard. Rapid transport of produce from distant regions also removed the need for local growers.

This continued well into the twentieth century and after the era of the Chinese gardens. After the Second World War, improved long-distance transportation of farm produce became an important cause of the decline of the food bowl in the Maitland area. Eventually, the production of many food crops such as potatoes, cabbages and cauliflowers ceased on the Bolwarra Flats, Pitnacree and elsewhere. Potato farming, for example, was out-competed by Tasmanian growers.

A Tasmanian potato crop in recent times

(Australian Broadcasting Corporation)

As the market changed, some Chinese gardeners turned to other trades or became fruit and vegetable shopkeepers. One Chinese man, known simply as ‘Jimmy Chinaman’, hawked cotton, silk and pins to East Maitland housewives: he had large cane baskets of these items on the ends of a pole carried on his shoulder. Young Yun became a storekeeper residing in Park St, 200 yards from War Lee, who also had a shop in the same street. Yun had a dominoes room (more probably a Mah Jong facility) attached to his shop, and the entrance to both was through a large opening in the front that did not have a door.

In 1902, Yun was robbed by a group of men. In the ensuing court case, one witness, Winifred Allen, 24, admitted she lived with Ah Cud at Louth Park and was in Young Yun's house on the night of the robbery. Her statement proved crucial for the success of the prosecution, presumably because she was European (Maitland Mercury, 5 November 1902).

After Federation and the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901, most gardeners realised the writing was on the wall. By 1910 they were pretty well gone from the Maitland scene. Ah Tui was the last.

References

Belcher, Mick ‘1868: Chinese Gardens arrive in Maitland area’, Our Past, Maitland Mercury, 5 March 2021

Maitland Mercury.

Newcastle Morning Herald.

The Australian.