Maitland’s steam trams

In the late nineteenth century, tram transport became the favoured means of moving people in numbers in Australia’s major urban centres. All the colonial capitals had trams, and before the turn of the century, a number of regional towns had acquired them or were aspiring to do so. In New South Wales, Newcastle and Broken Hill had trams by 1900, and in Victoria, Bendigo, Ballarat and Sorrento (on the Mornington Peninsula) were early tram towns.

Having a tram system, powered by steam or electricity, was a mark of urban status and municipal importance. They represented progress too: trams were faster than horse-drawn coaches and could carry many more passengers.

Unsurprisingly, Maitland sought to join the tram-town club. The existing railway operated at a regional level more than a local one: its services were infrequent and designed to serve through traffic to Newcastle and to the interior of NSW. Moreover the railway line and stations were not conveniently sited in relation to the shopping centres of High St and Melbourne St.

From early proposals to construction

There was a proposal for a Maitland tram line as early as 1893, a plan being drawn up for trams to link East and West Maitland and extend south via Heddon Greta and Kurri Kurri to Pelaw Main on the South Maitland coalfield. The idea came to nothing, but interest remained, and in 1901, the borough councils of East Maitland and West Maitland drew up a bill to allow them to form a company which would build and operate electric trams between the two towns.

This initiative lapsed too; the bill was never introduced to the state parliament. But local progress associations remained positive, and public meetings indicated continuing support for tram services. There was a deputation to parliament, and eventually the state government agreed to build a line beginning with a track from Victoria St in East Maitland to Hannan St in West Maitland. Extension to Rutherford and Pelaw Main could occur later if justified, the government argued.

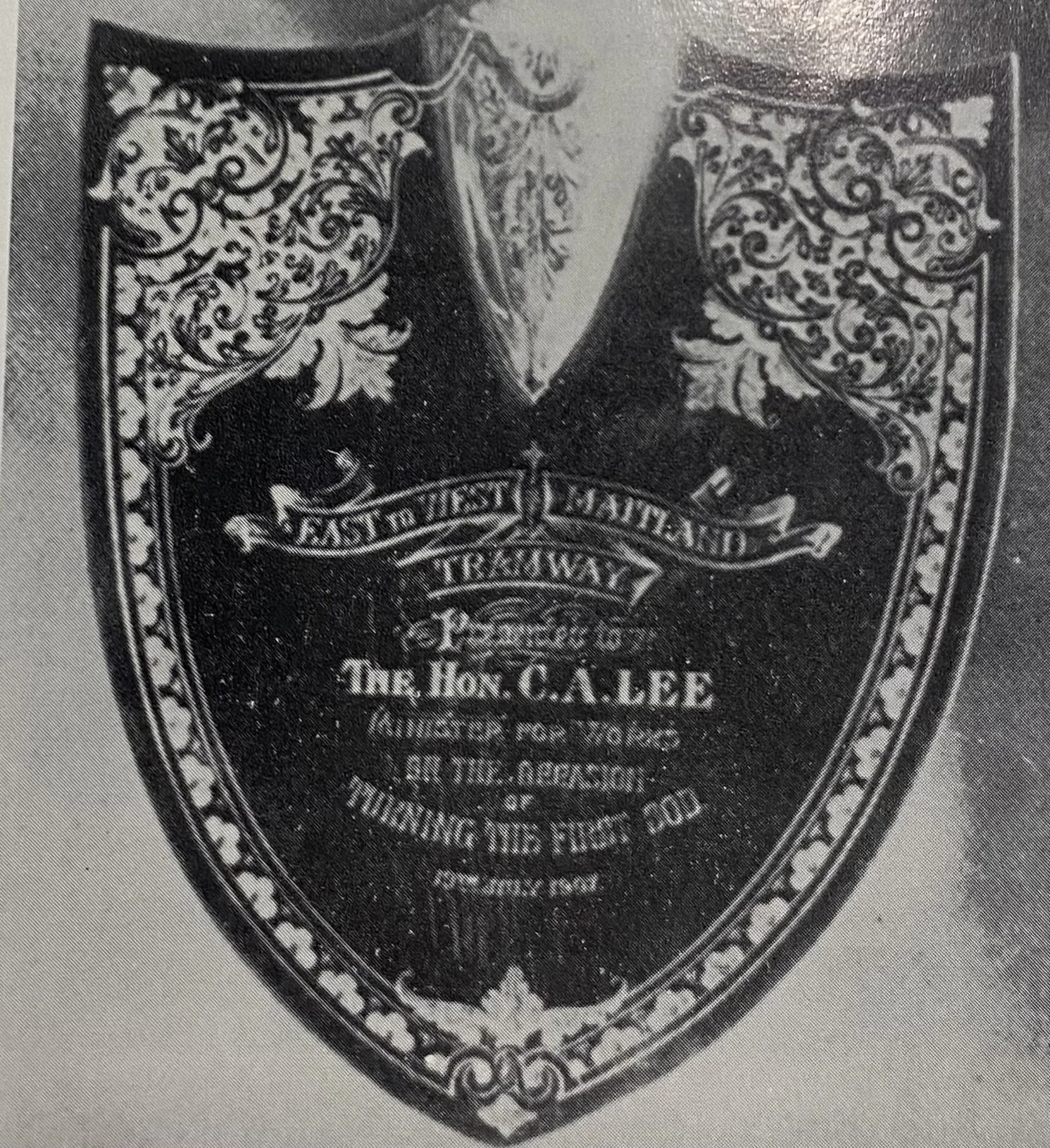

The government’s Railway Commissioners expressed concerns about the financial viability of the scheme. Nonetheless, an authorising Act of Parliament was passed in 1906. George Champion’s tender of £11,056 won him the job of constructing the track, and in July 1907, the first sod was turned at the corner of Victoria and Lawes streets by the Minister for Works, Charles Lee. People turned out in numbers for this event and, later, to witness the arrival and then the trialling of the motors and trailers.

The inscribed shovel used by the Minister for Works to turn the first sod, 19 July 1907.

Construction of the line took 18 months. Much work had to be done to fill in low-lying areas like the natural watercourses along or across George St, Victoria St and Lawes St. Men with horses and tip drays filled these areas with soil to build up the path of the track. The track’s cost was more than twice the originally tendered amount, but nobody worried much. Civic pride was running high: Maitland was about to become a tram town!

The opening

Opening day, 8 February 1909, was a grand ceremonial occasion, as the opening of the railway line from Newcastle and those of the Long, Pitnacree, Belmore and Morpeth bridges had been in earlier years. A public holiday was declared and thousands turned out, ladies in their finery, for the opening. At the corner of Victoria and Lawes streets, the wife of John Gillies, the MLA for Maitland, cut a ribbon held by the mayors of the two municipalities, JFH Walker (East Maitland) and Major Walter Cracknell (West Maitland). This was a moment of unity for two communities that were arch-rivals in many things.

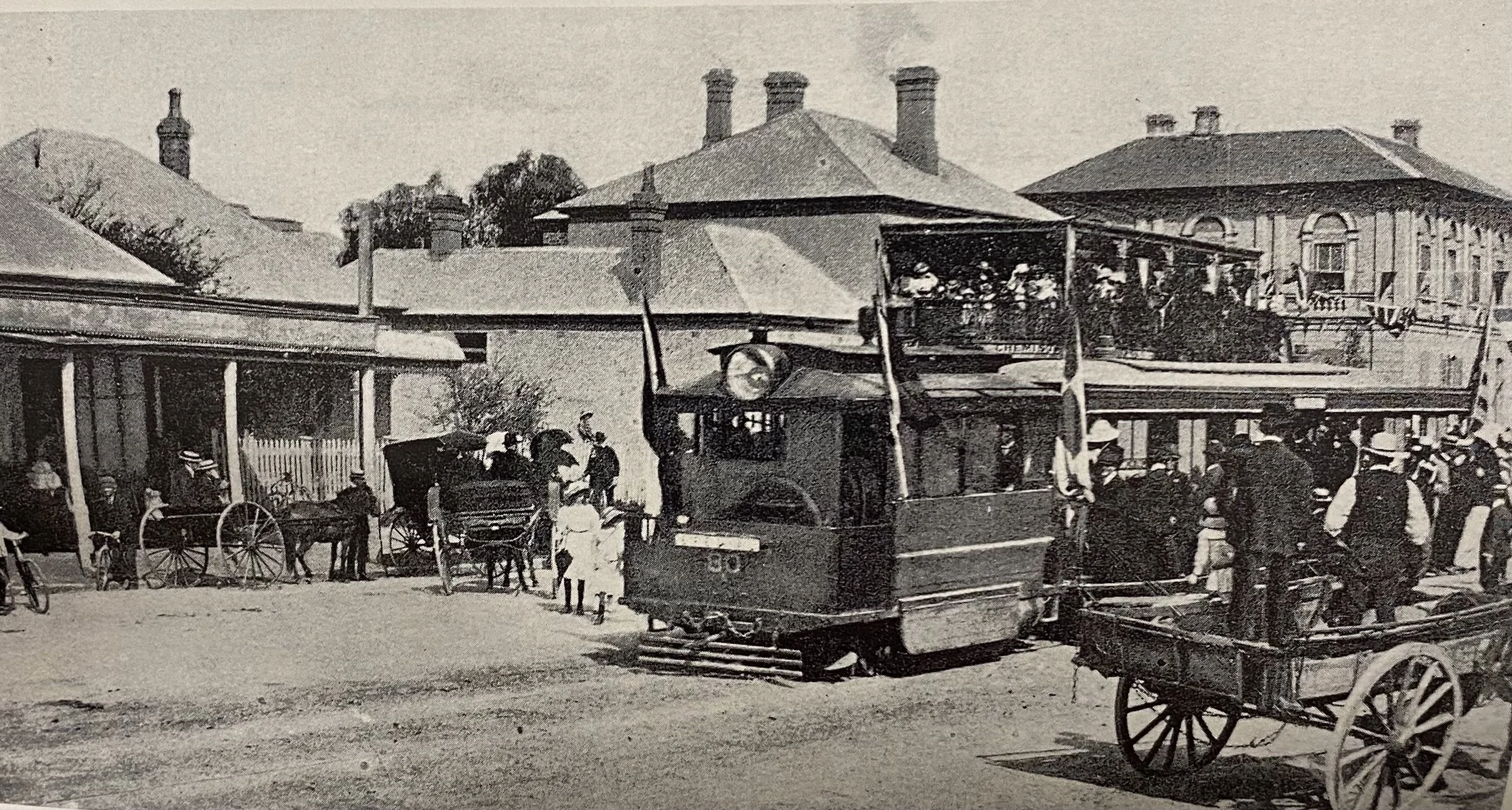

After the speeches, the flag-bedecked Motor 80A pulled a single trail car filled with dignitaries on the journey to West Maitland. The motor’s whistle blew constantly along the way and bands played. There was much joy to behold.

Opening day of tram from East to West Maitland, 1909

The first tram in Newcastle St on opening day, 1909

(K Magor Collection) (also Picture Maitland)

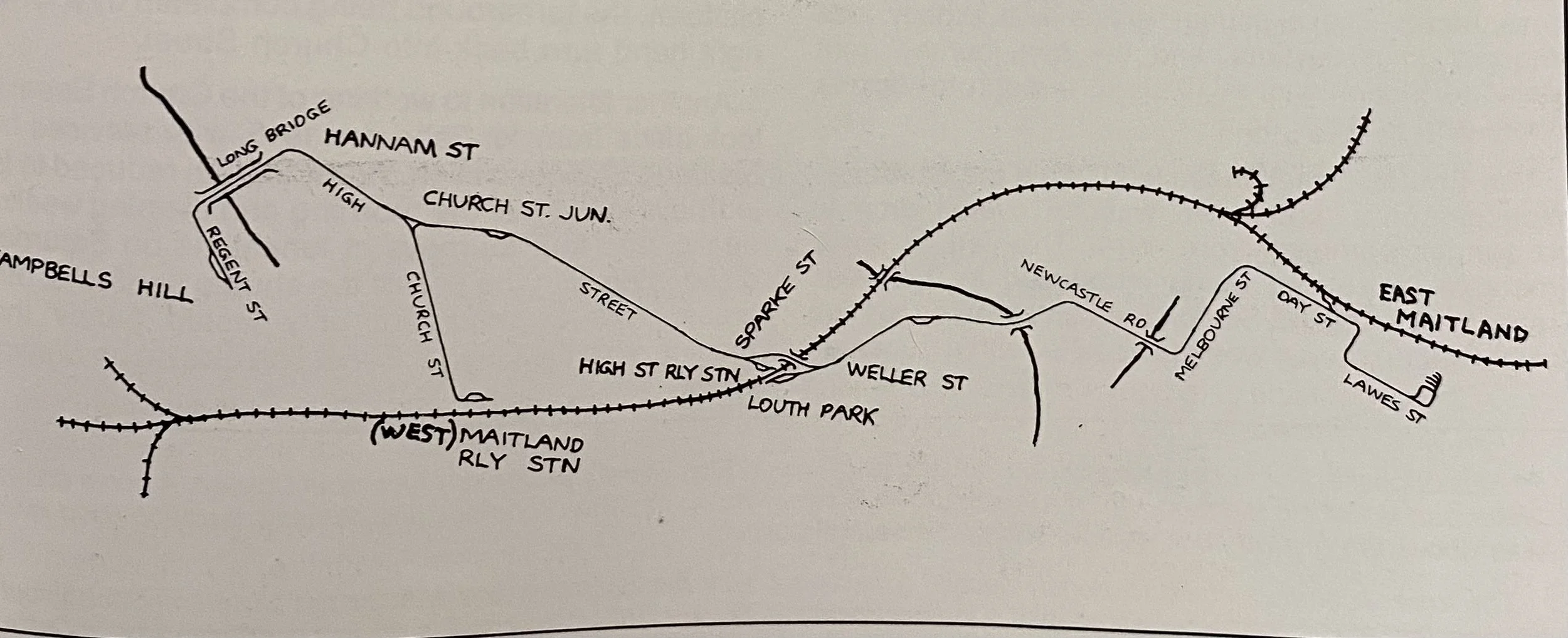

The line

Initially the line ran from the Victoria St terminus, near the intersection with today’s Hobart St in East Maitland, to Hannan St. From Victoria St the line ran down Lawes St to George St, into Day St and along Melbourne St to Newcastle St. It continued west across Wallis Creek over the Victoria Bridge and through the railway gates into High St, West Maitland. Traversing the length of High St to Hannan St (briefly the western terminus), the line was soon extended to Regent St, west of the Long Bridge. A special trestle was built on the Oakhampton side of the bridge to accommodate the tram line.

A tram crossing the Long Bridge to Campbell’s Hill

(Kerry photograph)

The track was now 4 miles, 5 chains (about 6.6 kilometres) long, with a loop near the site of today’s Visitors Centre to allow trams going in opposite directions to pass each other. The trip from one terminus to the other took 25 minutes and trams ran every half hour during the daytime.

In 1910, a spur line of 37 chains (roughly 740 metres) was added from High St along Church St to the West Maitland Railway Station. Five years later, the level crossing just east of the High St Station was replaced by a bridge over the railway line, and for a time a tram service operated on the railway line from East Maitland to Morpeth.,

Operation

The four motors and eight trail cars were housed under cover at the Victoria St depot. Light repairs and painting were undertaken there. More significant repairs and maintenance were carried out in Newcastle: a branch line connected to the railway line at Kings St, East Maitland, was used. Trams were permitted on the railway line only on Sunday mornings.

The engines’ furnaces were fired with coke from the Maitland Gas Works, on the site of today’s Reading Cinemas, before the drivers arrived for duty each morning. The fires had to be kept going by the drivers during their shifts. Conductors collected fares from footboards, which ran along the sides of the trail cars: these were open to the weather which must have made the task of the conductor unpleasant on wet or windy days.

The original line was divided into three ‘sections’ (Victoria St to Fitzroy St, Fitzroy St to the High St Station and High St Station to Hannan St) with the fare set at a penny per section. Sunday patrons were charged double. In 1914 the price for the first section was raised to two pence, Monday to Saturday. The eventual extensions to the West Maitland Station and Regent St were incorporated within the original sections.

The railway line through Maitland and the tram’s route at its greatest extent.

(MacCowan)

No trams operated on Sundays between 10.30 am and 12 pm or between 6.30 pm and 8.00 pm. These were ‘Church hours’: in those days church services were protected from what were deemed to be potential competing activities including sport and travel. Ironically, some people might have found the tram convenient as a means of getting to and from church.

Extra services were provided during major events, for example, during the annual Agricultural and Horticultural Show at the Maitland Showgrounds. On occasions, trail cars from Maitland went to Newcastle to cope with the extra traffic associated with special events (like race meetings), and the Newcastle system reciprocated during periods of high demand in Maitland. Such arrangements were facilitated by the fact that the two systems were both under the control of Newcastle’s Tramway Superintendent.

Maitland’s trams employed drivers (Messrs Horsfield, Carter, Druery, Pendle and Curry in the early years) and conductors (Messrs Lamb, Hills and Gulliver). A Mr McMahon was both a driver and a conductor. There were ticket inspectors, too, and clerical staff who worked in an office at the Victoria St terminus. No women ever worked on the trams themselves, but a few were employed at Victoria St.

Like any other infrastructural initiative, the trams had their operational problems. Sometimes they would jump off the rails when turning into Lawes St from Victoria St and had to be jacked back on. They occasionally left the tracks near the Victoria Bridge over Wallis Creek, too.

Train derailment, Maitland, about 1917

On busy late shopping nights in High St, with carriages full of people, the trams could not always make the steep turn from Day St to George St in East Maitland. They would have to go back down the hill, build up more steam and make another attempt. On occasions, muscle power from young male passengers was needed for them to complete the turn.

Tram at intersection of High St and Church St. The RJ Pierce Memorial Fountain at bottom right.

(K Magor Collection)

Trams at intersection of High St and Church St, West Maitland, about 1912

Left: Motor 32A, en route from West Maitland Station to High Street Station passes the Maitland Technical College in High Street, West Maitland, circa 1912. (Picture Maitland)

Right: Steam tram outside David Cohen and Co building, High St, about 1926. Sydney William Smith photograph. (Picture Maitland)

click on above images for larger views

The end of the era of the trams

Maitland’s trams operated until the end of 1926. Proposals to electrify them and to extend the line to Rutherford or to Kurri Kurri and Pelaw Main were never acted upon. In the end, the trams were unable to compete with the buses from the East and West Maitland Motor Bus Company. The trams never succeeded financially, and during the 1920s rising car ownership began to take an additional toll on patronage. Losses increased steadily, nearly doubling between 1922-23 and 1925-26. The Church St spur line to the West Maitland Station was a particularly dismal failure and lasted less than five years.

The state government eventually decided that the ‘costly and wasteful’ tram service would be closed, as the Broken Hill service and two sections of the Sydney system would also be. Lobbying from the Maitland councils failed to overturn the decision. Probably, the combined population of East and West Maitland and Morpeth (less than 12,000 in 1914) was insufficient to make the service viable. It is telling that Maitland was, apart from Victoria’s Sorrento (which had the advantage of being connected to Melbourne), the smallest centre in Australia to operate a tram service during the early years of the twentieth century.

The final Maitland tram trip took place on the last day of 1926, Rube Digby at the controls. He blew the tram’s whistle the whole way from Victoria St, and cars on the streets responded with their horns. It was an occasion of some community sadness, and the tramway staff organised a memorial function which, apparently, no aldermen attended. Probably they felt the closure, and their inability to prevent it, reflected badly on them.

The last tram departs for Newcastle, with ‘In loving memory’ and ‘Gone but not forgotten’ inscribed on the motor, 1926.

(RF Moag Collection)

Some staff members had worked for Maitland’s trams since 1909. A few of them were absorbed into the Newcastle tram operation.

The removal of the rails began in 1927 and the rolling stock went to Newcastle for use on that city’s service. One trailer car became a changing room at the Hamilton tennis courts. Some of the Victoria St sheds went to the North Kurri Railway Station and the office block was re-erected at Broadmeadow. A waiting shed at Fitzroy St was demolished by the flood of 1955. These days, extensive re-use of redundant facilities would probably not occur.

Today, little if anything can be seen of the tram’s presence in Maitland.

The tram had, during its lifetime, been an important piece of publicly-owned and operated infrastructure. Its linking of the two main parts of Maitland was important to the functioning of the place. It was a particular boon to East Maitland, greatly facilitating access to West Maitland’s High St, which was by far the main shopping area and principal place of employment in the whole Maitland area.

Maitland’s trams lasted less than 18 years. Probably, they were the folly of a small town wanting to be thought of as a big one. Newcastle’s trams, by contrast, operated from 1887 to 1950, and they have returned in recent times in the guise of the light rail service.

References

Gow, Arthur, Early East Maitland: the memories of Arthur John Gow, unpublished memoir, 1979.

Keys, Chas, ‘Our past: the steam trams that connected east to west’, Maitland Mercury, 14 October 2022.

Keys, Chas, ‘Our past: the demise of city trams’, Maitland Mercury, 24 February 2023.

Keys, Chas, ‘Our past: when Maitland joined the tram-town club’, Maitland Mercury, 3 March 2023.

MacCowan, Ian, The Tramways of New South Wales, the author, Oakleigh, 1990.

Willson, R and McCarthy, K, Maitland Tramway Ventures, South Pacific Electric Railway Co-operative Society Ltd, Sydney, 1965.