The shortening of the lower Hunter River

Today’s Hunter River floodplains are nothing like what they once were. Early European incursion saw the removal of the majestic cedars and the rosewoods and gums, important to building in Sydney and requiring the stripping of the casuarinas and other trees from the riverbanks to allow access to the more valuable species. Then came clear-felling of the remaining thick ‘brush’ to establish farms, first by the convict settlers at Patersons Plains and Wallis Plains and then on a much larger scale when the large rural estates were established from the early 1820s.

The imperative of creating a farming economy also saw the draining of large lagoons including Lake Paterson (between today’s Woodville and Wallalong, then called Butterwick), Lake Lachlan (in the Louth Park-Bishops Bridge area) and the semi-permanent wetland of Phoenix Park.

The responses of the Hunter to the changed vegetation and wetlands

The changes wrought were utterly transformative. The water storage capacity of the floodplain was reduced, runoff finding its way to the streams more quickly. Stream banks, denuded of soil-holding vegetation, collapsed, widening the channels and beginning a change from clear water in the channels outside flood times to water of greater turbidity (muddiness).

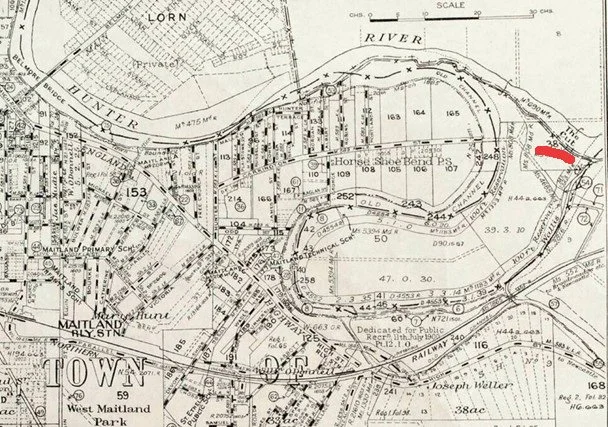

The river and its tributaries rose more quickly after heavy rain because less water was held in the bush. Moreover water flowed more quickly in the stream channels which speeded flows and enhanced bank erosion. The northern side of Horseshoe Bend was badly affected, a large promontory shaved off by aggressive flows during the frequent floods between 1857 and 1870. An island in the stream was swept away, as were roads and dwellings in the Bend itself. The shanty town of Irishtown adjacent to Horseshoe Bend disappeared because of this erosion.

The location of Irish Town

(Lawrie Henderson)

By the 1950s there was a fear that bank erosion would cause shops in High St to collapse into the river as had happened with houses during the nineteenth century. This concern led to the bank downstream of the Belmore Bridge being armoured with rocks and its slope made less steep. One consequence was that the river’s channel was moved slightly towards Lorn.

Work being done to reduce steepness of the river bank, central Maitland, 1962

(Michael Clarke)

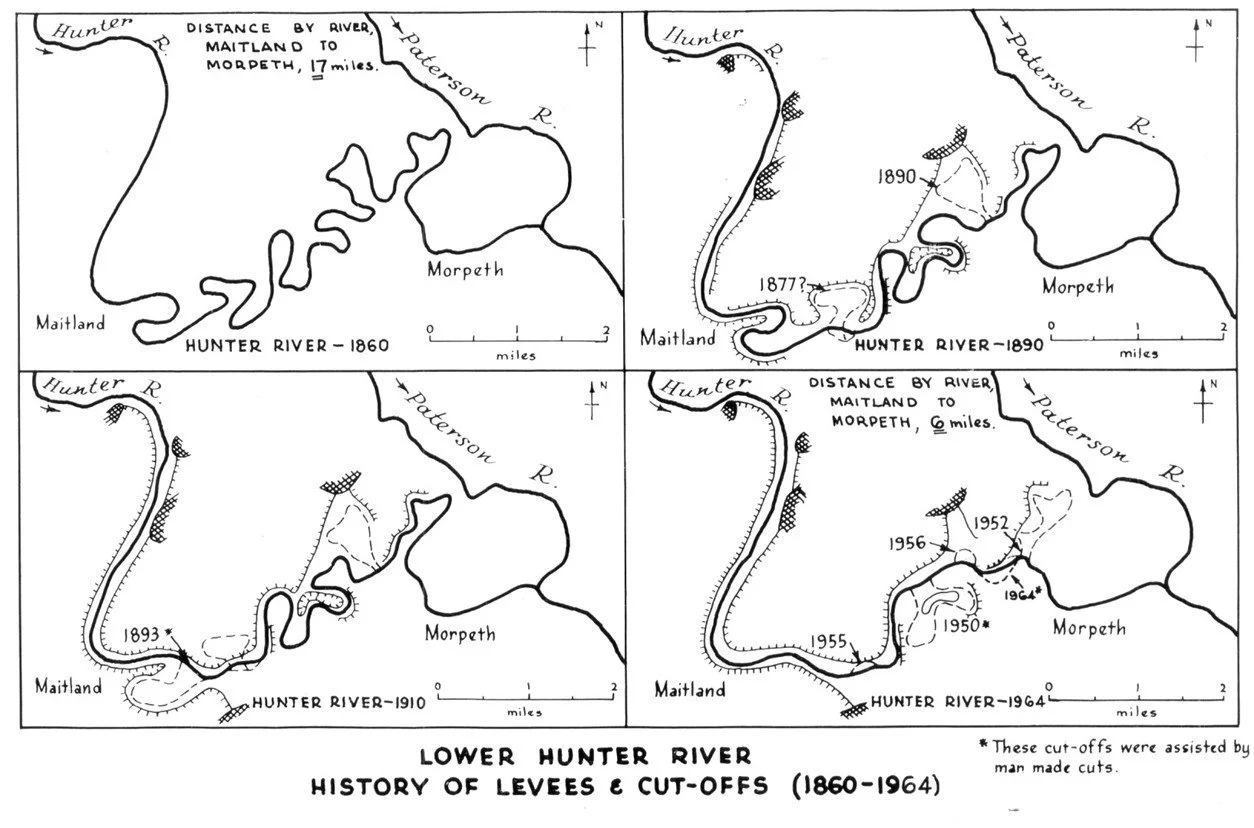

The severing of the meanders

Eventually, meanders were cut off at their ‘necks’. The first to go was the Pig Run meander, probably during a flood in 1879: the remains of the old channel can still be seen along Glenarvon Rd east of Lorn. Now steepened, the channel saw faster flows of water. Before long, in 1890, the King Island-Largs meander was severed too. The result was that Largs, previously a port town with its own wharf, no longer had a river-side location.

Next to go was the Horseshoe Bend meander, in 1893. In this case the severing was deliberately sought, a contractor hired by the West Maitland Council to dig a 240-yard (215-metre) channel eastward from downstream of Lorn to Pitnacree. This was known as ‘The Cut’. The intention was to accelerate flood flows past Horseshoe Bend and eastern High St and reduce the likelihood of floods entering residential and commercial areas. The 1893 flood finished the contractor’s task for him, creating a much wider channel than had been intended.

Map showing the Cut from Horseshoe Bend to Pitnacree: towards top on right hand side.

Further meanders were cut off during the flood-rich 1950s. Two Pitnacree loops went in 1950 and 1951, leaving the Pitnacree Bridge stranded over an abandoned, sand-filled channel. Narrowgut was severed in 1952. There were lesser cutoffs in 1955, 1956 and 1964, the last of them aided by flood mitigation work carried out by the Department of Public Works. In 1952 Taggarts Point, opposite Morpeth, was partially shaved off as the channel moved eastward by several metres.

The river’s course has been relatively stable since 1964, notwithstanding further erosion of the banks which has further widened the Hunter’s channel which has also become shallower.

The changing course of the Hunter River, 1860-1964

(NSW Department of Public Works)

Erosion and sediment build-up

Sediment build-up meant that channel carrying capacity was reduced, with the result that overflows onto the floodplain occurred in smaller floods than in previous times: flooding was in effect made more frequent. Hundreds of hectares of land were lost to bank erosion, rich alluvium built up over millennia being deposited in Newcastle Harbour where costly dredging was required to maintain the depths needed for ships there especially after 1950. The 1950s, a decade of many floods, saw the environment of the Hunter Valley at its most degraded in terms of the loss of forest vegetation. At about the same time ships using Newcastle Harbour to load coal were becoming larger and required greater depths of water to operate.

The problem of erosion still exists and the river’s main channel is still gradually widening. These days, about 500,000 cubic metres of silt are removed annually from Newcastle Harbour.

Against all this, faster drainage after floods facilitated the return of farmland to production. The loss of productive capacity due to waterlogging was reduced.

Over less than a century the river distance from Maitland to Morpeth was reduced, from 26 kilometres to nine, and the sinuosity of the river’s channel between the two towns declined markedly. The health of the Hunter River declined over the period and it has not recovered since.

Very little of the change that occurred to the river between the beginnings of European settlement and the 1960s, apart from ‘The Cut’, was intended and there would have been little appreciation of the environmental damage that was being done. From an ecological point of view there was more loss than gain from the change.

References

Belcher, Michael, ‘Our past: the forgotten history of Maitland’s ‘Irishtown’’, Maitland Mercury, 28 March 2023.

Bevan, Scott, ‘Clear water below’, Newcastle Herald Weekender, 21 October 2017.

Keys, Chas, Maitland, City on the Hunter: fighting floods or living with them? Hunter-Central Rivers Catchment Management Authority, Maitland, 2008.

Keys, Chas, ‘Our past: how the bends were removed over time from the Hunter River’, Maitland Mercury, 11 April 2021.

New South Wales Department of Public Works, Lower Hunter Valley Flood Mitigation Scheme, Government Printer, Sydney, 1964.