‘The Cut’ that severed the Horseshoe Bend meander in 1893

Of all the impacts of the Great Flood of March 1893 - the most damaging flood in Maitland’s history to that time - few were more spectacular than the severing of the Horseshoe Bend meander. The cutting off of the loop killed the already moribund Port of Maitland located on the site of the present Maitland Regional Athletics Centre, reduced somewhat the severity of floods in the business area of eastern High St, and dramatically changed the course of the Hunter River. It also led to facilities like the West Maitland Water Brigade’s boatshed being isolated from the river, and it facilitated the gradual westward movement of the Central Business District which had already begun to occur.

The making of ‘The Cut’

The severing of the meander had been sought by the Council of West Maitland for some time in order to hurry floodwaters past the town: getting rid of the water quickly was a key element of flood mitigation thinking at the time. An 1885 map shows the location of what was already known as ‘The Cut’ from Porter’s Point (east of Lorn) to near the position of today’s Harry Boyle Bridge. It was also known as the ‘Hunter River Relief Cutting’, the word ‘relief’ indicating the flood mitigation intention. With a grant from the colonial government of £1210/2/6 (equivalent to more than $200,000 today), a contractor (WH Sutton) was hired to excavate an 800-foot (240 metres) channel. Sutton’s was the lowest quote received. John Gillies, the MLA for Maitland, had lobbied the government hard for this money. It was one of the first of his many successes in obtaining government support for Maitland.

The location of the Cut

(Picture Maitland)

Only part of the task of creating ‘The Cut’ had been completed when the 1893 flood struck and scoured out the rest of the channel to four times its originally intended width. The flood also took with it Sutton’s horses, drays and excavating equipment. He suffered a double loss when the council refused to pay him, citing the flood as having done the job. Sutton promptly sued the council and won.

The Council had wanted to alleviate the pressure of floodwater on the town, especially eastern High St with its many business premises, by creating what would today be called a flood bypass. Straightening the river’s course, it was considered, would take the channel away from High St and quicken flood drainage. With drainage facilitated, post-flood recovery on the farms would be promoted as land became usable more speedily. This was the accepted wisdom of the day, and these consequences came to pass. But there were negative impacts as well.

The consequences

By 1893 the Port of Maitland was well past its 1830s-50s heyday, indeed barely functioning. The advent of the railway in the late 1850s had seen river traffic between Maitland and Morpeth decline to a fraction of its pre-1850s levels. The port in the Horseshoe Bend loop, once vital, had become increasingly incidental to the functioning of Maitland, and its formerly busy loading and unloading precinct had lost its purpose. Rail and road had replaced shipping in the movement of farm produce, manufactured items and people travelling to and from Maitland.

Among the lesser consequences of the river’s changed course were the loss of the community’s swimming pool on the Horseshoe Bend meander and the rowing club’s and Water Brigade’s facilities being left high and dry next to the former river channel which steadily silted up. Before long, that part of the old channel immediately east of today’s Athletics Centre, became a rubbish tip. Nearby portions were eventually to become the locations of Maitland’s major rugby league football field, created during the Depression of the 1930s as an unemployment relief project that filled in the former riverbed, and the City’s track and field facility now known as the Maitland Regional Athletics Centre. This centre was an upgrade of the former Smyth Field.

The Maitland Regional Athletics Centre (foreground) and Maitland Sports Ground today.

(Maitland City Council).

The trees mark the former riverbank of the Horseshoe Bend loop and the location of the first wharves of the former Port of Maitland

More significant in the long term than the loss of the swimming pool and the Water Brigade’s and rowing club’s facility becoming stranded was the westward migration of the CBD along High St. Freed from the tie to the port, which had been established with the building of wharves beginning during the 1820s, some businesses in what had been the most densely built-upon section of High St (from Ward St to Hunter St) relocated. Over decades from the 1850s they moved to the higher ground further west. This process was further ensconced as a result of ‘The Cut’. The old core of Maitland, on the eastern part of High St, was steadily transformed as it became increasingly peripheral to the CBD.

CBD investment in the form of new commercial buildings had, especially during the 1870s and 1880s, been focused on this higher ground. The 1880s alone saw the Maitland Post Office, the AMP Chambers, the large CBC Bank, the Capper’s Store and several other significant buildings constructed on sites a few metres higher than the level of eastern High St. Much of Maitland’s business heart thus achieved a measure of protection from floods: the buildings for about 200 metres west of Ken Lane’s Menswear (about 20 metres west of the High St-Bourke St intersection) suffered little or no over-floor inundation even during the great flood of 1955. That flood, like those of 1913, 1930 and 1949, did huge damage further east where several commercial and governmental functions still operated on lower ground as they had since the town began to form.

The port ceased to exist, having ‘lost’ the river, but some of the old CBD buildings stayed where they were - as they still do. Several of these buildings came to house public and welfare functions like Centrelink and St Vincent de Paul (‘Vinnies’) rather than the commercial activities for which they were constructed during the nineteenth century. The former Centrelink, for example, occupied what was once a store and warehouse operated by David Cohen and Co, in its heyday among the most important commercial establishments in Maitland.

The cutting off of the Horseshoe Bend meander was part of the decades-long story of the straightening of the river’s course, largely as a result of the river’s responses to the removal of the thick brush from the floodplain and the river’s banks. Several meanders were cut off over the following decades, the channel’s gradient was steepened, and flood flows became faster and more erosive of the banks and the fertile soils of the farmlands.

The politics of fighting floods

In West Maitland the cutting off of the Horseshoe Bend meander was welcomed. But some people downstream took a different view: in the Morpeth district (including Phoenix Park and Duckenfield) the idea of ‘The Cut’ was opposed because floodwaters would get away more quickly from West Maitland and arrive sooner in those areas. There would, it was feared, be higher flood levels downstream and worsened impacts by way of bank erosion and the resulting loss of valuable, fertile farmland.

And there were such consequences. Five months after the 1893 flood, the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate editorialised on the topic. It noted that, thanks to The Cut, the flood had arrived in the Morpeth area

… with greater velocity . . . the water higher than it otherwise would have been, [and] the banks along the Phoenix Park side were torn away.

The area had a number of tenant farmers on very small blocks - some of only ten acres - fronting the river: they would potentially have been badly affected by the loss of any of their land.

The paper continued:

The Morpeth people argue that if special provision is to be made to get the water safely past West Maitland it is only common sense to first strengthen the lower reaches of the river, so that floods can escape by a shorter route to the harbour at Newcastle.

That is, work should first be done to ‘improve’ the river’s capacity to remove floodwater from the lower areas. Only later should such work be undertaken upstream at West Maitland.

The lower areas had railed against similar Maitland proposals before. One suggestion had been to build a big ‘canal’ from Bolwarra to Largs to speed flood flows past the town. Another was for a canal from Louth Park via Howes Lagoon to Morpeth: this proposal had been advanced by a Sydney visitor, ‘KL’, in a letter to the Sydney Monitor as early as 1833.

These canals were never built, though in effect the levees of the modern flood mitigation scheme have created ‘flood overflow’ channels around Maitland.

The West Maitland interest prevailed over the interests of others. The concerns of the townsfolk outweighed those of the downriver farmers, who were in different council areas, and the agricultural benefits of speedily removing floodwaters were frequently cited in West Maitland.

The logic that was advanced on West Maitland’s behalf was not unreasonable: floodwaters needed to be drained quickly so farmland could be returned to a productive state as soon as possible. Sodden ground was useless to farmers and for the growing of food. Against that, any speedy removal of floodwaters that also involved the loss of good farmland to erosion was hardly an optimal solution. Focusing on reducing the duration of flooding to the exclusion of other concerns would produce inequitable results and intensify community resentments.

Phoenix Park, soaked and temporarily unproductive, after the 1955 flood

(Ray McDermott)

Criticism of a government department’s ‘apathy and neglect’

The whole question is a most important one, and its solution is certainly not made more easy by departmental apathy and neglect. (Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate)

This was a hit at the Department of Public Works, which had conducted studies of the problems caused by floods but was not greatly involved in fixing them.

Probably this was because in the 1890s, flood mitigation was not yet a cause that the colonial government had embraced with much vigour. Action was left to farmers’ co-operative bodies like the Bolwarra Embankment Committee and to shire and municipal councils, so the measures adopted were likely to suit some localities and interests rather than others. A comprehensive, planned, region-wide approach, as distinct from purely local endeavours, was to wait until after another great flood - the flood of 1955.

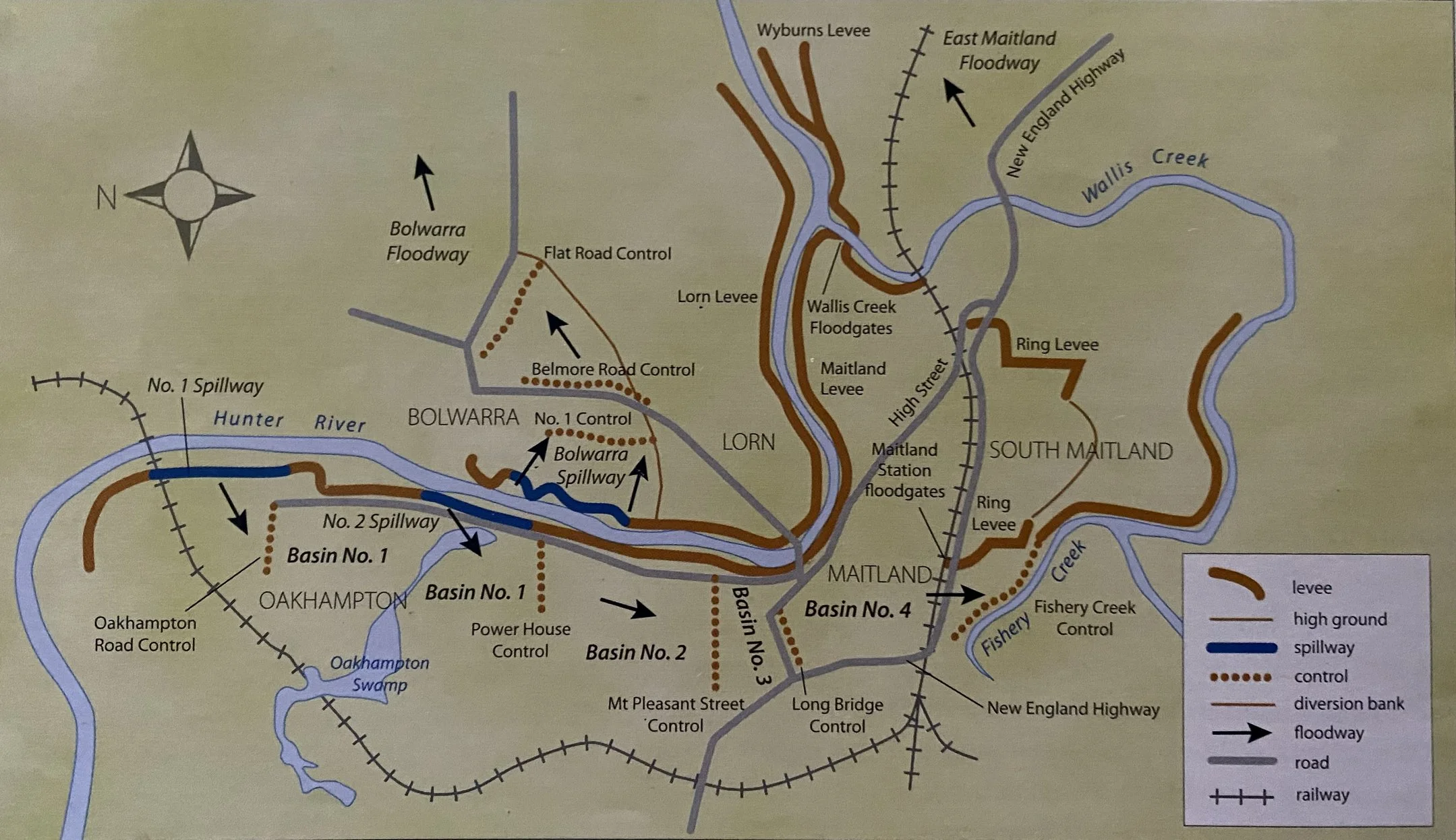

The Department of Public Works was to be much involved when the modern flood mitigation scheme was developed between the late 1950s and about 1980. Canals, though, were not to be part of the scheme which focused instead on the construction of improved levees and on ‘training’ floodwaters over spillways in the levees and across farmlands. Farms in the Bolwarra, Oakhampton and Louth Park areas thus became the sites of flood bypasses. This was not necessarily welcomed by the farmers in these areas, who felt that they were being forced to pay part of the price of protecting the interests of townspeople.

The levees and spillways of the modern flood mitigation scheme

(Department of Public Works)

The scheme has not had the deleterious impacts of ‘The Cut’.

References

Keys, Chas, ‘Our past: the severing of the Horseshoe Bend meander in 1893’, Maitland Mercury, 17 September 2020.

Keys, Chas, ‘Our past: the Morpeth objection to ‘The Cut’ at West Maitland in 1893’, Maitland Mercury, 12 February 2021.

Maitland Mercury.

Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate.

Turner, John, The Rise of High Street, Maitland: a Pictorial History, second edition, The Council of the City of Maitland, Maitland, 1989.