Jocko Graves: Maitland’s ‘Little Black Boy’

Jocko’s story

On a cold Christmas night in 1776 during the American War of Independence, General George Washington and his small army are about to cross the Delaware River at McConkey’s Ferry in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Their goal is the British garrison in the New Jersey town of Trenton. The garrison is well armed and fortified while Washington’s men are near mental and physical exhaustion.

Legend has it that among the 60 free African Americans who had joined Washington’s cause was a man called Tom Graves. Graves had a 12-year-old son named Jocko who wanted to join the fight alongside his father, but he was of course too young. He went anyway.

As Washington was preparing to cross the Delaware he realised he would need to leave his horses. Young Jocko volunteered to hold them until Washington returned. He was also asked to hold a lantern to guide the soldiers back after the battle.

Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851

So cold was the night that the next morning young Jocko was found frozen to death, still holding the tethered horses and the lantern. The story continues that his sacrifice and heroism restored the hope and valour of the reinforcement troops, inspiring Washington’s men to victory over the British garrison. Only four rebels died on that fateful night, two killed in battle and two who froze to death. Young Jocko was one of the latter.

The statue

After the War, and upon becoming the first President of the United States, Washington is reputed to have ordered that two sculptures be erected on his Mount Vernon (Virginia) estate. The first was a ‘Dove of Peace’, the second a young African-American boy named Jocko, stepping bravely forward to hold the horses. Washington was apparently moved by Jocko’s heroism and his sad death, and he called the statue the ‘faithful groomsman’.

It is from this story that the so-called ‘Lawn Jockey’ statues evolved, Maitland’s ‘Little Black Boy’ on High St among them. Jocko’s statue is 33 inches (about 84 centimetres) tall, hollow and of moulded (cast) iron. The same and similar statues are found in many places in the United States, and it is said in some quarters that they played a role in guiding escaping slaves to freedom via the ‘underground railroad’ to the northern states. This version of the story has it that the statues were used to indicate safe houses in which runaways could hide from the men who were hunting slaves down for return to their masters. In this guise the lawn jockey became a symbol of freedom.

Photographs of Maitland’s statue

left: (John Turner Collection, Living Histories, University of Newcastle)

right: (Percival Steinbeck Collection, Living Histories, University of Newcastle)

A few of the statues of Jocko have appeared in Australia. There is one in Inverell, and long ago there was one in Sydney’s York St. There is also a fibreglass replica kept in storage in the Maitland Regional Art Gallery. It was fashioned by Ken Pryor in East Maitland in 1971.

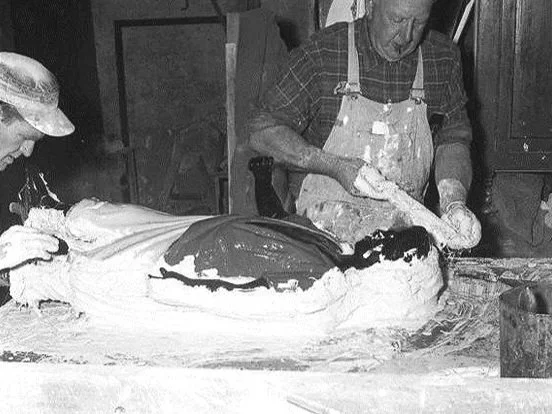

Ken Pryor taking a mould of the original cast iron statue, Pryors Plasterworks, 1971

(Athel D’Ombrain Collection, Living Histories, University of Newcastle)

The statue in Maitland was originally designed as a hitching post with pipes inside its mouth to produce a spurt of water which could be caught by a trough at the base. Somehow the water feature was never incorporated in the Maitland statue.

The original statue was brought to Maitland by Friend & Co, a Sydney ironmongery firm, and erected in front of the firm’s High St premises probably in the mid-1870s. In 1886 it was standing in High St, opposite Elgin St, in front of Harrison & Co. Friend & Co closed down in 1895, three years after Archibald Down MacDonald had bought the statue and relocated it to the opposite (southern) side of High St in front of his tobacconist and newsagency which is today a vape store. In all likelihood, MacDonald probably wanted a sales gimmick to attract custom to his store. It is possible that the original statue was located elsewhere in High St at times. There are several theories as to the statue’s history but the full truth remains uncertain.

Wherever he was on Maitland’s main street, Jocko had a practical purpose as a hitching post for horses. Today he is one of the few remaining cases of a hitching post, a reminder of the days when horses and horse-drawn vehicles were the main means of getting about other than on foot. Since his arrival in Maitland, Jocko has graced the local streetscape except for when he was knocked over by cars and trucks and damaged.

In 1971, the statue was stolen from High St by two young men in a drunken prank. The perpetrators took it to Sydney, but they soon recognised their folly and returned it to its proper location. Before that the statue had periodically been knocked over and damaged by vehicles in the street. Various repairs were made, and the statue’s story over the years after the Second World War has been traced by historian Jack Paten in his recent The Maitland Black Boy. Fibreglass replicas were made, but the version now at the High St/Church St corner is of cast iron.

Today’s statue is probably largely the original, but the body shape has been changed slightly. Probably it was partially remodelled during the 1950s at a local foundry. It stands guard near the corner of High and Church streets outside what were once MacDonald’s premises.

Jocko Graves statue being replaced, Maitland,

(Athel D’Ombrain Collection, Living Histories, University of Newcastle)

click on above images for larger views

Jocko’s place in Maitland life

Jocko has witnessed much of Maitland’s history, from before Federation, steam trams and Les Darcy to the world wars, the 1955 flood, and the making and re-making of High St. He has been dressed in school uniforms, the colours of racehorses and people’s favourite sporting teams (in particular Maitland’s Pickers rugby league club, formerly the Pumpkin Pickers), and at one stage he was spray-painted white. It is said that returned soldiers from both world wars made ritual pilgrimages to greet him. For them, perhaps, meeting up with the ‘Little Black Boy’ was part of coming home to Maitland from the horrors of war.

Men going off to fight, too, took note of him. One member of a group of soldiers, heading overseas, is said to have made a speech hoping that they (the soldiers) would do their duty as well as Jocko had done his.

Jocko was also a favourite of children who spoke to and patted him on passing by.

The evidence is that Jocko has been regarded with affection by generations of Maitland people. Over the decades he grew to be a part of Maitland and he developed a place in people’s hearts. Probably, thousands have patted him on the head, given him a hug or had a quiet, fond word in his ear.

In days gone by, the ‘Little Black Boy’ was featured in many tourism brochures and pamphlets, Maitland City Council letterheads and any number of company advertisements. Souvenir spoons, postcards and tea towels bearing his image were also produced and he appeared in 1983 in a major council-commissioned history of Maitland. Newcastle country and western singer Bryan Watkins recorded a bush ballad (Maitland’s Black Boy) about him around the same time.

left: A Jocko badge (Jennifer Buffier Collection)

right: The front page of the 1972 Maitland phone book (Maitland and District Historical Society)

There was a time when anything to do with Maitland was thought incomplete without an image of the ‘Little Black Boy’ to accompany it. Today, though, Jocko’s story seems not to be as well known as it once was. In fact, he has become a slightly forgotten figure in Maitland. People see him, don’t know what his story is and have to ask about it. It was not always thus. Jocko has faded somewhat from the consciousness of Maitland.

Jocko with broom

(Athel D’Ombrain Collection, Living Histories, University of Newcastle)

A controversy emerges

In the twenty-first century, there are different views of who and what Jocko represents. According to the legend of the boy who helped Washington, he was the son of an emancipated African-American slave who joined the fight for independence and freedom against the tyranny of British colonialism. In this guise he is a symbol to inspire the oppressed to rise up and be heard. He is also a symbol of courage and devotion to duty.

From a different perspective, Jocko’s presence on High St in a role that could be considered subservient is seen as a symbol of inequality and racism. In a debate in Maitland City Council in 2023, the statue was referred to by one councillor as a ‘racist garden gnome’, ‘provocative’ and not helpful in terms of the maintenance of social cohesion in Maitland. This perspective taps into debates about what to do with statues and monuments that, while products of their times, can be seen as reinforcing stereotypes or celebrating less savoury aspects of the past.

Jocko is a part of Maitland’s streetscape and has been for a long time. His significance in the history of High St needs to be explained. So too does the legend that attaches to his origins and so too do those views that perceive a stereotyped black child.

It was said that there is no evidence to validate the legend of Jocko Graves, and that is true in terms of documented material. But not all truth is verifiable via the written word; there are other means by which knowledge is transmitted down through the generations. The lack of written evidence does not mean that Jocko’s story as passed down orally to today is untrue – or indeed true. Nor does the fact that the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University, Big Rapids, Michigan has incorporated the Little Black Boy in a collection of racist artefacts mean that the statue itself is or represents a racist depiction. The museum clearly takes a different view.

We need to be careful here. ‘Cancelling’ the depiction of a black American boy who was possibly born into and might have experienced the horrors of slavery cannot be allowed, whatever one’s view of the nature of the depiction, because getting rid of it would imply that no depiction of slaves is permissible. Better, surely, to argue that horrors involving the treatment of human beings by other human beings can legitimately be displayed as part of ensuring we understand and remember what they were. Indeed, this is part of trying to ensure the horrors are not repeated.

It is one thing to cancel somebody who is known only for heinous activity ꟷ for example, a slave trader with no known positive contributions to the human condition ꟷ by removing his statue from a town square or his name from a national park. This has been done with the former Ben Boyd (now Beowa) National Park in south-eastern NSW. But it is entirely another matter to withdraw recognition from somebody who oral history records as having acted heroically. There is a strong argument that we should not get rid of Jocko merely because he was the son of a recently-emancipated slave. Nor must we accept that in the statue he is playing a subservient role. His role in 1776, as mentioned in the version of the story of his involvement in the War of Independence noted in the first section of this article, was important to a cause which today is widely recognised as having been legitimate especially in the USA.

There is a part-parallel between Jocko’s story, passed down orally and with no written information to corroborate it, and the transmission of Aboriginal traditions from generation to generation. We should not deny information that is passed down this way: in the Aboriginal case that would mean denying songlines about creation, nature and history. All Aboriginal stories come from an oral tradition. Australia would be the poorer if the standard we adopted was to be based on a denialist approach to Aboriginal communication: we would in effect be saying that Aboriginal stories and Aboriginal history were non-existent and without value. We would also be encouraging their loss when it would surely be wiser to encourage their preservation.

Loss of stories and history, in this context, would be tantamount to the undermining of Aboriginality itself.

More than a decade ago, there was a fibreglass copy of a statue of Jocko in the Maitland City Council’s administration building but for reasons unknown it disappeared. In 2020, the Council received a petition seeking the removal of the statue from the High St-Church St intersection along with a similar statue located inside the Mutual Bank building: apparently more than 500 people signed it. Perhaps, though one can’t be certain, a genuine plebiscite conducted after people had been informed about the legend of Jocko would show that a majority of the residents of Maitland would support him staying exactly where he is. Discussions on Maitland’s Black Boy on Facebook appear to support that view.

In late 2023, a motion that the Council look into the declaration of the statue as a heritage item under the Maitland Local Environment Plan was passed. The argument was put by a bloc of four councillors that the statue is a symbol of racism and thus unworthy of heritage status, but nine councillors took a different view. The reality of the vote made neither version ‘right’ nor ‘wrong’, but it provided a kind of resolution to the controversy and a way forward for Council.

Jocko with Maitland City Councillor Mitchell Griffin, 2023

(Newcastle Weekly)

A way forward

It is time Council added a plaque or some signage to the statue to explain the story of Jocko as passed down over the decades, so that he can be recognised in the community for the heroic role he might have played on the bank of the Delaware River in 1776. It is not necessary to believe that there is racism involved in his story, though some have argued the opposite case. The Little Black Boy is American, but he is part of Maitland’s history too and there is nothing definitive to be ashamed of or defensive about.

Jocko deserves to be understood and celebrated in the Maitland main street he has graced for decades. For this to happen, his place in the community’s consciousness needs to be restored.

References

Coleman, Chloe, ‘‘Racist garden gnome’: Jocko’s status debated’, Maitland Mercury, 28 July 2023.

‘Here It Is!’ World News, 22 July 1954.

Keys, Chas and Kevin Short, ‘Historic case for little Jocko’, Maitland Mercury, 25 August 2023.

Koger, E Snr. Jocko: a legend of the American Revolution, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1976.

Lefall, Waymon E, Jocko a long way from home down under, Page Publishing, New York, 2014.

Maitland and District Historical Society A History of Maitland, The Council of the City of Maitland, Maitland, 1983.

‘No Reins for Outstretched Hands’, Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 19 August 1950.

‘Old Movie Bill Found in Statue’, Newcastle Sun, 11 August 1953.

Paten, Jack. The Maitland Black Boy, the author, 2024.

Scanlon, Mike. ‘The mystery of the multiple Maitland landmarks’, The Hidden Hunter, the author, Newcastle, 2021.

Short, Kevin, ‘Our past: a symbol to inspire the oppressed to be heard’, Our Past, Maitland Mercury, 3 December 2021.