Changes to vegetation and wetlands

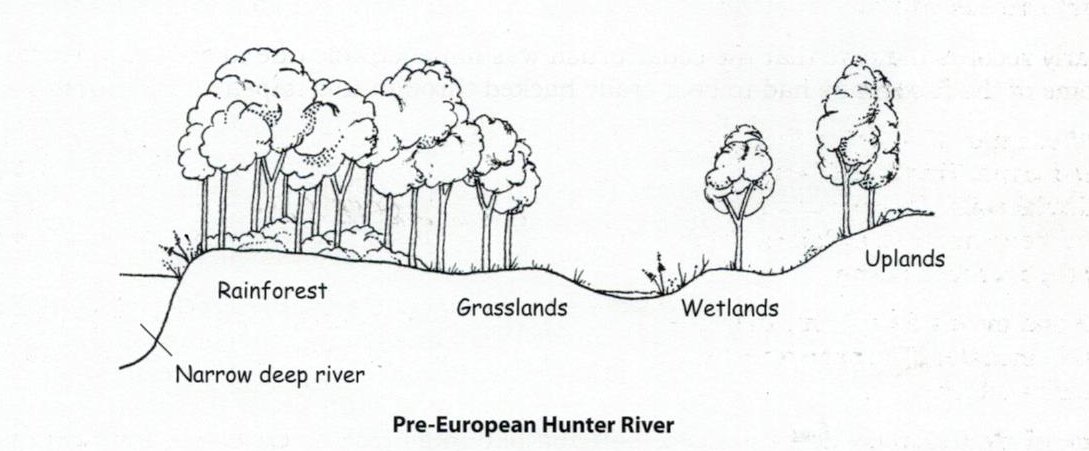

Of all the environmental modifications created in the Maitland area by Europeans in the nineteenth century, none were more far-reaching than those wrought to the vegetation on the floodplain of the Hunter River, the home of the cedars. The lower reaches of the valley’s sides, which were covered in eucalypt forests interspersed with grasses, were also considerably altered from their pre-existing state. Moreover, the lagoons on the floodplain were drained as a means to create more farmland.

What the early colonists needed

The imperatives for the colonists were, from 1801, to fell the cedars for timber and soon after (especially after European settlement in 1818), to create an agricultural economy. The thick brush of the floodplain had to be removed to make room for grasses and crops. Secondarily, removing the thick vegetation facilitated travel across the floodplain.

Contemporary accounts indicate how radically the vegetation assemblage was altered. One individual, using the pseudonym ‘Memory’, wrote a letter to the editor of the Maitland Mercury in 1877 in which he detailed the situation in the 1820s before wholesale vegetation removal got under way on the just-created large estates. Here is an excerpt from Memory’s letter:

I can . . . well recollect the imposing and magnificent appearance of the dense brushes which covered the greater proportion of the splendid estates now known as Berry Park, Bolwarra, Phoenix Park, Wallalong, Dunmore, Hinton, &c . . . Magnificent indeed was their appearance. Gigantic gum trees towered far and away above all others, and spread their radiating and mighty limbs far and wide like umbrellas over the green ocean of lovely foliage, which crowned the tops of the closely wedged mass of their smaller brethren. And less lofty, but still imposing and inconceivably beautiful, were the fig trees, which in many instances were of enormous size . . . The whole of the large cedar trees had long before the period of which I write disappeared, but the huge stumps remained as evidence of their vast proportions . . . So thickly did the timber grow that it was often very difficult to proceed . . .

The replacement of the riverbank she-oaks and the dense floodplain brush, much of it rainforest, with pasture grasses and crops was completed within a small number of decades. Huge trees were felled, and their stumps rotted away or were burnt out. The impacts were utterly transformative, much more so than the Aboriginal fire-stick farming which had earlier increased the amount of grass cover especially on the sides of the valley.

The river’s responses

The river responded radically to the changes. More water ran off to it after rains than before and did so more quickly, less runoff was retained on the floodplain and floods rose more rapidly. The banks, denuded of the trees that held them together and now grazed by cattle, became unstable and were eroded. Silt built up in the river channel, the river steadily became wider and shallower and its water more ‘turbid’ (cloudy with suspended matter) thanks to the silt load it carried.

Turbidity was exacerbated later when European carp invaded the river and ‘grazed’ on its banks, further reducing their stability. All these changes were detrimental to the health of the river.

Many hectares of fertile farmland were lost over the decades, soil deposited in huge volumes in Newcastle Harbour and requiring costly dredging to remove. Eventually, some of the soil from farms on the Maitland floodplain was used in reclamation initiatives to join and build up the estuary islands downstream of Hexham and on the Newcastle foreshore.

Meanwhile the many floodplain lagoons including Lake Paterson near Woodville and Lake Lachlan (from Lochend and Louth Park to Farley) were drained during the 1820s and 1830s to convert wetland to farms. The environment was radically altered once more, with species that had depended on the wetlands largely disappearing, though nature routinely reclaimed the wetlands during periods of flooding. Habitat for water birds was greatly reduced.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the environment of Maitland and surrounding areas was unrecognisable from what it had been before the arrival of Europeans. Especially on the floodplains, virtually nothing remains of the original vegetation assemblages. Massive changes were quickly and irreversibly created during the 1800s and an essentially artificial environment was fashioned.

(Walsh and Archer, p 9)

(Walsh and Archer, p 9)

References

Keys, Chas, ‘Our past: How European settlement led to Maitland losing its cedar and eucalypt forests’, Maitland Mercury, 6 September 2020.

Walsh, Brian and Archer, Cameron, Maitland On the Hunter, second edition, CB Alexander Foundation, Tocal, 2007.